From

'A Season in Hell, Ravings I, Foolish Virgin, The Infernal

Bridegroom'.

From a book of Collected Poems by Oliver Bernard. This poem is about

Verlaine, but Rimbaud wrote it!

Voice-over Verlaine, to open the story in Total Eclipse:

he speaks of Rimbaud.....

'Sometimes he speaks

in a kind of tender dialect. 'Sometimes he speaks

in a kind of tender dialect.

Of the death which causes

repentance,

of the unhappy man who certainly exists;

of painful

tasks and heart rendering departures.

In the hovels where we got drunk, he wept,

looking at those who

surrounded us; the cattle of poverty.

He lifted up drunks in the black

streets.

He had the pity a bad mother has for small children.

He

moved with the grace of a little girl at chatechism,

he pretended to

know about everything;

business, art, medicine. I followed him, I had

to.'

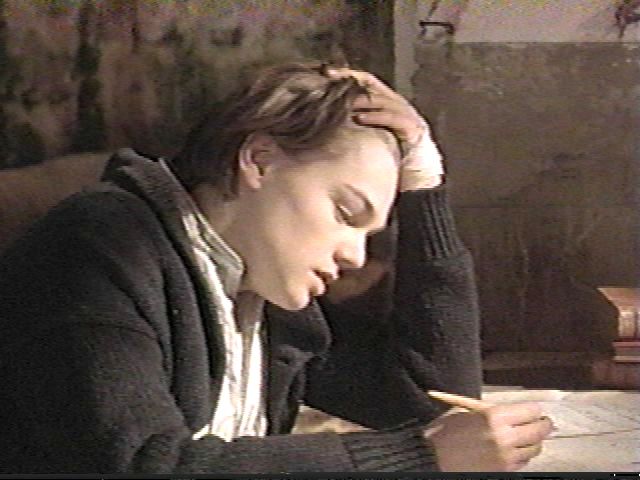

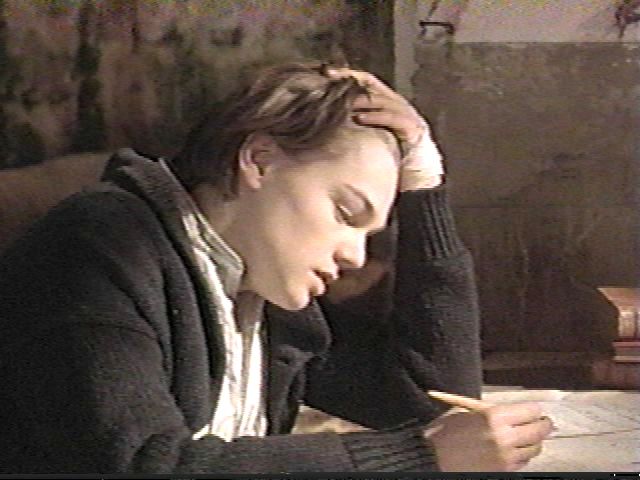

My love for TBO's portrayal of the character Arthur

Rimbaud in Total Eclipse, has inspired me, and many loyal DiCaprio

admirers to delve a little deeper into Rimbaud's life and works. Through

my friend, Annabelle, who kept me up to date with a writer named "Enid

Starkie" and her insightful book about Rimbaud, I have decided to share

some of what we have learned about this long ago genius.

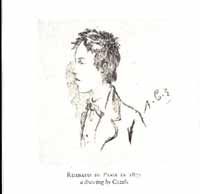

For starters, only one

third of Rimbaud's work has been found. They use the word 'Rimbaudisms' in

the book. Certain words were invented by Rimbaud and Verlaine in their

conversations with each other. These "Rimbaldism-slogans" were used by the

students involved in the Student Revolution of 1968 in Paris! For starters, only one

third of Rimbaud's work has been found. They use the word 'Rimbaudisms' in

the book. Certain words were invented by Rimbaud and Verlaine in their

conversations with each other. These "Rimbaldism-slogans" were used by the

students involved in the Student Revolution of 1968 in Paris!

Expressions like 'angel' and 'devil' come up frequently when people

(who knew him) talk about Rimbaud, and isn't that exactly how Leonardo

brought him to life?

Rimbaud actually said: "O Verlaine.....Verlaine.." when he came

back to Roche after the shooting, when Verlaine ended up in prison.

Verlaine, who only went along with Rimbaud on his road of life for a

short distance, knew him, loved him, and understood him.

He considered

his 2 years of imprisonment as a 'holy task', he was preparing the

publication of 'Poetes Maudits' (1884)and later of 'Les Illuminations'

(1886).

About his poetry:

Rimbaud succeeded, with astonishing certainty of

touch, in adopting and making his own the technique and the methods of

composition of the masters of his day, and in so doing he learned his

trade.

An explanation for his frequent use of 'bad language' in poems and in

his speach:

Later it will become apparent that whenever Rimbaud was

subjected to any unusual strain this showed itself outwardly in the

coarseness of his speech or writing. Izambard used to say that after a

dispute with his mother, Arthur would become scatological in his

conversation, but never otherwise.

Before Rimbaud leaves for

Paris he writes to Izambard (his teacher). He ends the letter with: Before Rimbaud leaves for

Paris he writes to Izambard (his teacher). He ends the letter with:

... I enclose some verses of mine. Read them one morning in the sun,

as I wrote them. You are no longer for me a teacher - at least I hope not.

Good-bye and send me a letter of twenty-five pages, very quickly, poste

restante.

A. Rimbaud

PS..Very soon I shall give you some startling news of the kind of life

I'm going to lead after the summer holidays.

This is how he 'escaped':

On 28 August, three days after he wrote to

Izambard, he was walking with his mother and the two little sisters in the

meadows on the banks of the Meuse. Suddenly he left them saying that he

wished to go home to fetch a book to read. It was not, however, home that

he went, but to the station, and boarded the first train leaving for

Paris. He's fifteen at the time and very childish and puerile....

He boarded the train without a penny in his pockets and set off thus

for Paris.

It is easy to picture his

wretched mother's anxiety and distress when she arrived home and found

that her son had not reached the house, and, like every monther in similar

circumstances, she imagined all manner of hideous possibilities. It is easy to picture his

wretched mother's anxiety and distress when she arrived home and found

that her son had not reached the house, and, like every monther in similar

circumstances, she imagined all manner of hideous possibilities.

Nothing was heard of him until his spirit was broken and all his

courage had ebbed away.

He than wrote to Izambard:

Cher monsieur: What you advised me not to do I did, I left home and

came to Paris.

I love you as a brother, and I'll love you as a

father.

Your poor Rimbaud

PS...And if you come to Mazas (where Arthur is imprisoned because he

didn't have money to pay the trainticket!), you'll take me back with you

to Douai, won't you? (He just doesn't want to go back to his

mother..)

Izambard comes to the prison and pays the debt and takes

Rimbaud with him.

A few days later Rimbaud arrived at Douai, somewhat humiliated and

shamefaced, but happy nevertheless, to have got out of his scrape so

easily. He gave a lurid and highly coloured account of his adventures, his

arrest, his cross examination, the disinfecting of his clothes on his

arrival at the prison, and the terror he had felt when he had been locked

into his cell. Now that everything was over, he enjoyed recounting his

experiences and found therein outlet for his descriptive talent. It is

said that the poem, 'Les chercheuses de Poux' (the lice seekers), composed

in Paris the following year, refers to the ministrations of Izambard's

'aunts' when they cleaned his hair of the lice acquired in prison.

But his mother writes a letter to Izambard and Rimbaud has to go back

to Charleville.

Nothing could raise Rimbaud's spirits during the long and tedious

journey from Douai to Charleville. Terrified at the prospect of the

reception that was awaiting him at home, he sat huddled up in the corner

of the carriage and did not open his lips.

After dispatching his business Izambard left Charleville for some days.

He found, however, on his return in the first week in October, a letter

from Madame Rimbaud begging him to come to her aid once more as she was at

her wits' end with anxiety. Arthur had run away again and she had no idea

where he could have gone.

Rimbaud goes to Charleroi, then on foot to Brussels, and then back to

Douai.....

Izambard found him there after looking for him in Charleroi

and Brussels. He found him sitting in the parlour in the midst of the

aunts, quietly copying out his poems, with the neat writing and scrupulous

care of the model pupil. He was clean and tidy and looked so supremely

happy that Izambard had not the heart to scold him as he deserved,

especially as the aunts were obviously pleased to have him to look after

and to spoil.

The poems of this period

show a happy innocence and a purity that he never again recaptured. The poems of this period

show a happy innocence and a purity that he never again recaptured.

But he has to go once again: When he saw that his master had come and

that it was really time to go he said good bye to the aunts and promised

them faithfully that he would be good. They had grown very fond of him and

did not like to see him leave, for they had not found him difficult or

troublesome, on the contrary; with kindness and affection, he became once

more the good little boy he had been in the past who asked for nothing but

love and understanding.

On the way to the police station Izambard, out of his deep affection,

spoke to him seriously of his concern for his future, of the fame that

could await him, if he did not spoil his chances of all that he hoped from

him. As he spoke he could not keep the emotion from appearing in his voice

and it seemed to him that Arthur understood and was touched. But he could

never know with Rimbaud, for the boy was always tongue-tied and awkward

whenever he was stirred to feeling. Then Izambard handed him over to the

care of the police sergeant and that was the last time he ever saw

him.

Shortly after he reached home Rimbaud wrote to him:

Monsieur, for you

alone this. I came back to Charleville the day after I left you. My mother

received me and I am here completely idle. It seems that she won't put me

to school as a boarder until Jan 1871. Well! I've kept my promise. But I'm

dying and deliquescing in the dullness, in the drabness, and in the

foulness around me. Monsieur, for you

alone this. I came back to Charleville the day after I left you. My mother

received me and I am here completely idle. It seems that she won't put me

to school as a boarder until Jan 1871. Well! I've kept my promise. But I'm

dying and deliquescing in the dullness, in the drabness, and in the

foulness around me.

You see I still persist in loving liberty and a lot of things like

that. All very pitiable isn't it? I was going to run away to-day, and I

could have run away. I had new clothes and I would have sold my watch and

then long live liberty! But I stayed, I stayed. And yet I longed to run

away, many, many times. Here goes! With my hat, my coat, and my hands in

my pockets, I'm off. but I'll stay, damn it, I'll stay! I didn't promise

as much as that, but I'll do that to deserve your affection. you said that

to me and I'm going to deserve it. The gratitude I feel for you I can no

more express it to-day than I could the other day. But I'm going to prove

it to you. If it were only a question of doing something for you, I would

die to do it. I give you my word of honour. I have a lot of things to

say...

Your "heartless"

A. Rimbaud

When Izambard tells him he is leaving the school, Rimbaud is

desperate:

'What on earth shall I do when M. Izambard is gone? One

thing is absolutely certain and that is that I'll not be able to endure

this life for a whole year. I'll run away. I know how to write. I'll

become a journalist in Paris!'

And a friend asks: 'How will you

be able to fight your way alone?'

Rimbaud: 'Well! Then I'll fall

by the wayside! I'll die of hunger on a heap of stones, but I'll run

away!'

When Izambard leaves, Rimbaud is sunk in grief, the first passionate

grief of his life.

He was not yet sixteen, nevertheless this marked the end of his

school-days, for when the autumn came he had become another person and had

broken entirely with his old life.

At this state: his poetry had no positive faults, it showed remarkable

achievement, but there was nothing in it to give promise that he was to

become one of the most daringly original writers France has ever

possessed!

The more I read about him, the more interested I get. He must have had

a very strange life, very exuberant in the beginning and not very

interesting after he stopped writing poetry. It is so strange that he

wrote all these things 'in a kind of rage' (his sister Isabel's words) and

then just stopped writing. And he never bothered about his poems

anymore.....

The Cheated Heart

My poor heart dribbles at the stern, My poor heart dribbles at the stern,

my heart covered

with caporal:

they squirt upon it jets of soup,

my poor heart

dribbles at the stern:

under the jibes of the whole crew

which

bursts out in a single laugh,

my poor heart dribbles at the

stern,

my heart covered with caporal!

Ithyphallic, erkish, lewd,

their jibes have corrupted it!

In the wheelhouse you can see graffitti,

ithyphallic, erkish, lewd.

O abracadantic waves , take my heart that it

may be cleansed!

Ithyphallic, erkish, lewd, their jibes have corrupted

it!

When they have finished chewing their quids, When they have finished chewing their quids,

what shall

we do, o cheated heart?

It will be bacchic hiccups then:

when they

have finished chewing their quids:

I shall have stomach heavings

then,

if I can swallow down my heart:

when they have finished

chewing their quids what shall we do,

o cheated heart?

May 1871

'Le Coeur Supplicie' - 'The Cheated

Heart'

Had the College de Charleville been able to open that autumn term

Arthur Rimbaud might have given up his bohemian ways and have settled down

to regular work. The war, however, was being continued and most of the

teachers of the school were either at the front or else acting as special

constables. The greater part of the pupils, moreover, came from the

district now occupied by the Prussians.

For Arthur Rimbaud this

life of enforced idleness, with no fixed occupation, was disastrous. All

might have been well had he been able, as he wished, to enlist as a

soldier, but he still looked far younger than his sixteen years and he was

always turned down. In company with Delahaye he spent his days in long

country rambles, in interminable discussions on literature and especially

on politics. For Arthur Rimbaud this

life of enforced idleness, with no fixed occupation, was disastrous. All

might have been well had he been able, as he wished, to enlist as a

soldier, but he still looked far younger than his sixteen years and he was

always turned down. In company with Delahaye he spent his days in long

country rambles, in interminable discussions on literature and especially

on politics.

It was here, and at this time, that Rimbaud was fast gathering the

impressions that were to become later the substance of

'Illuminations'.

It is as if in the midst of the war and destruction

around him, he felt with a new intensity the extraordinary beauty of the

countryside which he had come to take for granted.

During this time he also read Verlaine's poems. And he added Verlaine

to his 'heroes'. Before ever meeting him, Rimbaud had learnt much from him

of the craft of poetry.

Even boys of Rimbaud's age were affected by the general spirit of

revolt symptomatic of the dissatisfaction which was suddenly to burst out,

not many months later, in the Commune. He was developing a hatred of all

government, of all authority, and this flame was fanned into activity by

his growing resentment of his mother's severe discipline. He would

willingly then have welcomed all form's of destruction, so long as

Charleville and the life he knew could be swept away to ruin.

Mezieres, where Delahaye

lived, was bombarded on 20 December and the town caught fire. That day

Madame Rimbaud locked all her brood into the flat, allowing none of them

to venture forth in the streets for fear that she might lose one of them;

ever since Arthur's escapades she was in constant anxiety about them.

Delahaye and Rimbaud were now separated and Rimbaud suffered an agony of

suspense on his friend's behalf, since no news had come, except a vague

rumour that his house had been burnt to the ground and that the whole

family had perished in the flames. Mezieres, where Delahaye

lived, was bombarded on 20 December and the town caught fire. That day

Madame Rimbaud locked all her brood into the flat, allowing none of them

to venture forth in the streets for fear that she might lose one of them;

ever since Arthur's escapades she was in constant anxiety about them.

Delahaye and Rimbaud were now separated and Rimbaud suffered an agony of

suspense on his friend's behalf, since no news had come, except a vague

rumour that his house had been burnt to the ground and that the whole

family had perished in the flames.

However, a neighbour informed him that the whole family had been saved

and were being given hospitality by relations in the country. Rimbaud's

only concern was now to reach Delahaye, and to bring him some books to

occupy his time. In spite of the danger he made his way to the farm that

was sheltering the family, bringing with him as an offering his most

recent discovery, Baudelaire's translation of Poe's works and Le Petit

Chose of Daudet. He hid the emotion and anxiety he had felt on his

friend's behalf beneath an expression of gruff and hearty cheerfulness and

would not allow him to express his gratitude for the attentions he had

received. It was ever thus with Rimbaud. In him, as in his mother, emotion

rarely expressed itself in outward manifestations, and he was always

embarrassed when others sought to thank him or to show their appreciation.

Now the situation in Paris is getting tense.

The National Guard now began to give trouble and to organize the

revolt. On 29 January they attempted to set up a military dictatorship ,

but the authorities discovered the plot through their spies, and the

leaders were arrested and condemned to imprisonment.

News of the activities of the National Guard reachted the provinces and

it was then that Rimbaud decided to go once more to Paris, this time to

help in his country's fight for liberty. (,,,,) His desire to leave

Charleville was increased by the fact that, the school having reopened,

his mother is expecting him to resume his studies.

His friends return to school but:

Rimbaud was scornful of

the action of his friends, declaring categorically that he would not

return to school, that there were other and more important things to do at

this crisis in the affairs of France He sold his watch and on 25 February

he left for Paris. Rimbaud was scornful of

the action of his friends, declaring categorically that he would not

return to school, that there were other and more important things to do at

this crisis in the affairs of France He sold his watch and on 25 February

he left for Paris.

Rimbaud had somewhere got hold of the name and address of Andre Gill,

the famous caricaturist, and with his habitual coolness, due to a complete

lack of knowledge and experience of worldly matters, he arrived unknown

and unannounced at the artist's studio. Gill was not then at home but the

door of his room was, as always, unlocked. Rimbaud entered and, being

tired after his journey, he lay down on the divan and was soon fast

asleep. It was thus that Gill found him on returning later. When he pushed

open his door, he stopped on the threshold and looked with amazement at

the huddled, untidy figure asleep on his couch. His first thought was that

it must be a burglar, then looking again he saw that it was only a child.

He shook the sleeping boy to awaken him and said, 'Who are you and what

are you doing here?'

Rimbaud sat up bewildered at having been suddenly

roused and answered, rubbing his eyes, that he was Arthur Rimbaud from

Charleville, a poet who had come to Paris to make his living. Gill was

touched by his extreme youth and his appearance of a lost child. He was

kind-hearted and gave him ten francs, all the money he had in his

possession that day, but told him that there was nothing in Paris for a

poet during these troubled times and advised him to go home to his

mother.......

At a certain point

the National Guard was preparing Paris to resist the tyranny of the new

government: Things were beginning to look exciting in the capital and

then, for some unexplained reason, Rimbaud departed and returned to

Charleville. It is impossible to understand what it was that persuaded him

to leave the capital just then when the fight, which he had come to see

and to help, was reaching its critical stage. It is probable that some

startling experience shocked and terrified him, driving him home for

refuge. All through his life, much as he disliked home, Rimbaud always

returned there for shelter. At a certain point

the National Guard was preparing Paris to resist the tyranny of the new

government: Things were beginning to look exciting in the capital and

then, for some unexplained reason, Rimbaud departed and returned to

Charleville. It is impossible to understand what it was that persuaded him

to leave the capital just then when the fight, which he had come to see

and to help, was reaching its critical stage. It is probable that some

startling experience shocked and terrified him, driving him home for

refuge. All through his life, much as he disliked home, Rimbaud always

returned there for shelter.

Delahaye always said, and others have repeated it after him, though the

grounds for holding the opinion have never been stated, the 'The Cheated

Heart' which Rimbaud enclosed in a letter to Izambard on 13 May was

written after he returned from the Commune and that it is the account of

the treatment to which he had been subjected at the barracks of the Rue de

Babylone, when he is said to have been assaulted by the soldiers.

What

is certain is that the poem is the outcome of some very bitter and painful

experience which left an indelible mark on him.

Up to now Rimbaud had

remained, in spite of his intellectual maturity, a child in experience,

who had been carefully sheltered from the ugly side of life. It is true

that like all imaginative children he had thought much about love and

passion, but only in a literary manner. It is quite obvious from the poems

he had written before April 1871 that he had as yet had no sexual

experience and singularly little sexual curiosity; even his imagination

had remained innocent and child-like. The only person ever to have stirred

his emotions was Izambard and his affection for his master was shy,

unexpressed and probably not fully realized by himself. At sixteen, when

he went to Paris, he still looked like a girl, with his small stature, his

fresh complexion and his reddish-gold wavy hair. It is probable that he

then received his first initiation into sex and in so brutal and

unexpected manner that he was startled and outraged, and that his whole

nature recoiled from it with fascinated disgust. But it was an experience

that did not leave him indifferent, nor his senses untouched. It was a

sudden and blinding revelation of what sex really was, of what it could do

to him, and it showed him how false had been all his imagined

emotions. Up to now Rimbaud had

remained, in spite of his intellectual maturity, a child in experience,

who had been carefully sheltered from the ugly side of life. It is true

that like all imaginative children he had thought much about love and

passion, but only in a literary manner. It is quite obvious from the poems

he had written before April 1871 that he had as yet had no sexual

experience and singularly little sexual curiosity; even his imagination

had remained innocent and child-like. The only person ever to have stirred

his emotions was Izambard and his affection for his master was shy,

unexpressed and probably not fully realized by himself. At sixteen, when

he went to Paris, he still looked like a girl, with his small stature, his

fresh complexion and his reddish-gold wavy hair. It is probable that he

then received his first initiation into sex and in so brutal and

unexpected manner that he was startled and outraged, and that his whole

nature recoiled from it with fascinated disgust. But it was an experience

that did not leave him indifferent, nor his senses untouched. It was a

sudden and blinding revelation of what sex really was, of what it could do

to him, and it showed him how false had been all his imagined

emotions.

He returned to Charleville a changed being, shattered and

enlightened by the experience through which he had gone, and he was never

the same again.

When Izambard got the letter with the poem he did not realize what had

been happening to his pupil; he did not understand the poem, nor how much

it had meant to Rimbaud.....

Izambard in replying to Rimbaud makes fun of the poem:

What is certain is that after this, Rimbaud shut himself away from

Izambard and made him no more confidences. The close friendship which had

been the deepest emotion of Rimbaud's boyhood was now at and end.

Le Voyou (meaning 'scoundrel' or 'raggamuffin')

Rimbaud returned home (from Paris) on 10 March in a state of

psychological turmoil and distress and this manifested itself outwardly in

the unruliness of his behaviour. He refused to wash any more and he

allowed his hair to grow until it hung in dirty, untidy ringlets over his

shoulders; he used to wander up and down the chief streets of Charleville

in the most crowded hour of the evening, the time of the 'aperitief', in

his dirty clothes, with his unkempt hair, his hands in his pockets (!),

smoking a short pipe and, what was considered most outrageous of all,

smoking it with its funnel pointing downwards!

In April the College the Charleville finally opened its doors in its

own building. Madame Rimbaud begged her son to return to his studies with

his friends, and again he refused to have anything more to do with

scholastic learning. It is during this time that he used the name 'La

Bouche d'Ombre' (the Mouth of Darkness) - his disrespectful name for his

mother, after the ponderous metaphysical poem by Victor Hugo, on account

of the weighty and religious nature of her frequent utterances.

So he didn't go to school anymore.

Rimbaud was, however, enjoying at the time a spurious popularity and he

had many acquaintances who were only too ready to encourage him in his

unruliness. He hung about the cafes for the larger part of the day,

waiting to find someone kind enough to offer him a drink of a fill of

tobacco, and he paid for these with the biting irony and ready wit which

he had latterly developed and which his hearers always found entertaining;

they appreciated particularly the contrast between the obscenity of his

language and the childishness and innocence of his face.(h how

marvellously our angel portrayed these Rimbaud characteristics!)

Rimbaud was now trying to break away fom all restrictions, mental,

physical and moral, and he used to claim to have no principles. Delahaye

relates that he (Rimbaud) would invent lewd stories about himself,

attributing to himself monstrous and repulsive actions and he used then to

be overjoyed when people sitting near him in a cafe would get up and leave

the table.

Yet all this only tends to prove his pitiable state of inner turmoil;

all this violence and obscenity seemed to have its roots in the utter

desolation within him, in a deep-seated wound.

For almost a year now, ever since he left school the previous summer at

the age of fifteen (!), he had been living under acute nervous strain. He

had seen the crash of the Empire and war at home; his native town had been

bombarded and he had gone in fear for the safety of one of his closest

friends (Delahaye); he had lost the company of the only person in whom he

had perfect confidence and trust (Izambard). All stability had departed

from his life, all discipline had been relaxed; he had run away from home,

had lived in Paris in the most abject poverty and he had encountered the

most searing experience of his life. All this was sufficient to upset the

equilibrium of a more strongly balanced youth than Rimbaud.

In the most brutal manner and without previous preparation, Rimbaud had

been faced with the problem of sex and he had been shocked, stunned and

obsessed by it. Hitherto he had only thought about love; it was an emotion

that flowed and emanated from him, but did not yet need a vessel to

receive it.  There is great innocence

in his early love poetry. He imagined that his love would ultimately be

directed towards some woman, like those of whom he had read in the poets

he admired. But no girl had ever looked at him or taken him seriously. He

was too shy, and looked too much of a child, with his rosy cheeks, his

curly hair, and his cracked, uncertain voice of an adolescent. But now his

senses were awakened and his body left curious and hungry for

satisfaction. He made one pathetic effort to gain experience, but he set

about it clumsily and failed. This is what Rimbaud wrote to a friend in

May 1871 about this effort: He described an assignation he had made with a

girl older than himself, the daugher of a magistrate. He had asked her to

meet him in the square at Charleville, but she did not come alone; she was

accompanied by her maid, and he said that he had remained as dumb and as

terrified as 'seventy-six thousand new-born puppies'. The girl had

been cruel and heartless; she had made fun of him, of his childish

appearance, his shyness and his shabby clothes..... There is great innocence

in his early love poetry. He imagined that his love would ultimately be

directed towards some woman, like those of whom he had read in the poets

he admired. But no girl had ever looked at him or taken him seriously. He

was too shy, and looked too much of a child, with his rosy cheeks, his

curly hair, and his cracked, uncertain voice of an adolescent. But now his

senses were awakened and his body left curious and hungry for

satisfaction. He made one pathetic effort to gain experience, but he set

about it clumsily and failed. This is what Rimbaud wrote to a friend in

May 1871 about this effort: He described an assignation he had made with a

girl older than himself, the daugher of a magistrate. He had asked her to

meet him in the square at Charleville, but she did not come alone; she was

accompanied by her maid, and he said that he had remained as dumb and as

terrified as 'seventy-six thousand new-born puppies'. The girl had

been cruel and heartless; she had made fun of him, of his childish

appearance, his shyness and his shabby clothes.....

Of course Rimbaud was hurt: His pride was always like an open wound, he

had no armour against humiliation, and now embittered by his experience

with a woman, he turned against the whole sex with disgust, and vowed that

he despised them all! Most of his poems at this time express a disgusted

obsession with women, a morbid horror of all that is woman.... (like' the

Sisters of Charity').

|